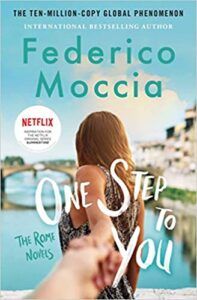

As an American with a lot of stamps on her passport and a few languages on her transcripts, I thought I was decently non-ugly. I don’t mean my looks, but Ugly American as a(n unfortunately rather accurate) stereotype — the kind of person who travels the world but arrogantly demands that everything be available in English and that breakfast include eggs, a person who insults foreign things abroad but culturally appropriates at home. Given that I am routinely asked to justify my presence in the country of my birth, that I am assumed to be an immigrant because of my last name, that I am expected to let strangers touch my hair or ask me about my heritage graciously, that I am all too familiar with people affecting accents, dress, or mannerisms to make fun of cultures that are not theirs, I thought I had a pretty good awareness of what it means to be ugly and did not typically behave that way. I thought I was reasonably non-demanding of American comforts abroad. Ugly Americanness is very much linked to white privilege, and while I have other sorts of privilege, that’s not one of them. Take my recent adventures in Italian. I’ve been learning it on and off through Duolingo and Pimsleur for the past two years or so. I traveled to Italy in the summer of 2019 and tried to ask for directions in the language whenever possible. I was demanding about food only insofar as my food allergies and intolerances were concerned and did not whine about different customs. I follow Italian pop playlists on Spotify, and I have Netflix foreign television watch parties with two Italian-speaking friends. I have a number of middle grade and YA novels in Italian and from Italy, and were they not packed away in a storage unit with the rest of my books, I would maybe pick them up and read them. And therein starts my crisis. Presently our little club is working our way through Summertime, an absolutely delightful teen series about teen angst and growing pains — universal problems — with a diverse cast and a beautiful setting. The general setup is this: the main characters are townies in a beach town, and our main character, Summer (who hates her name because it’s in English and who hates summertime because…she just does — our group chat is called “odio l’estate” in honor of Summy) has gotten a summer job at a resort hotel. She keeps running into a Bad Boy With A Sensitive Side, and it turns out he’s the boss’s son (and he has his own angst about wanting to quit motocross racing and having an overbearing father who doesn’t want to let him). She’s got a guy best friend who is crushing on her, a girl best friend who is queer and carefree (hooray for no lesbian tragedies!), a kid sister who isn’t annoying, and a very young mom who is just trying her best. The show is based on a book series by Federico Moccia, “the Nicholas Sparks of Italy,” and it is a WORLDWIDE BESTSELLER. I have never heard of it. Basically, the show came up when I searched Netflix for things in Italian, and it looked cool, and it was only in my subsequent IMDb research that I learned of its literary origins. So why did I not know of this YA series when I am such a YA aficionado? Oh. BECAUSE IT WAS NOT AVAILABLE IN ENGLISH. That’s right, folks. A global phenomenon has not been available in English and that does not, to my (your?) surprise, make it any less global. A whole lot of the world speaks languages other than English, and they are equally valid and valuable. This is humbling, seriously. It’s not like I consciously think the whole world needs to accommodate Americans, but I am so used to being catered to that it’s jarring that to find I’ve been left out of the club. Apparently readers of Italian, Spanish, French, Polish, German, and tens of other languages have been members of this book club since 1992, and I’ve been sitting here in my English-language, vaguely-competent-at-other-languages-but-couldn’t-survive-a-professional-or-academic-environment-with-it bubble completely out of the loop. I don’t even know where I could find a copy of the book Tre Metri Sopra il Cielo (literally “three meters above the sky”) if I wanted to try to read it in Italian. One Step to You, its first English-language edition, dropped this month, 29 years after its initial publication in Italy. What else have I been missing? This ugly American wants it all. (Good thing there is a Read Harder Challenge task that will help me rectify this!)

That’s not the only club I’ve been denied admission to.

Let’s keep going with Summertime. The first episode threw me because everyone was dressed like it was 1995, riding skateboards, but they also all had smartphones. It felt disjointed, and I didn’t understand what I was looking at. Then I realized that’s because Zoomers are wearing ’90s fashion right now! The ’90s are now! I’m just not a Zoomer, so I side-part my hair, wear skinny jeans, and use laugh-cry emoji. What I’m looking at onscreen is not weird, it’s just The Youth, and it’s also Another Country, and all of my shock is an Ugly American and Ugly Grownup reaction, not something legitimate. People my parents’ age keep telling me I’m young and to stop acting as if my life is over. I read children’s and YA literature professionally (and for fun!). I have canned elevator speeches so I can call people out when they act snobby about YA books. I still have a couple years to pop out a baby. I am youthful! The world is my oyster! Look, I teach Zoomer college students. Let me tell you: they don’t consider me their peer. They don’t understand my movie references or jokes, so they and Summertime confirm that actually, I am An Old. I am also not European. I watch the kids on Summertime going to parties and bars and I have this twinge of “that looks like so much fun” and a simultaneous twinge of “these CHILDREN are at a BAR; let me CLUTCH MY PEARLS. They should be IN BED and drinking MILK.” Clearly I am having trouble with this nowhereland I have found myself in — The Land Of Being In Your 30s. Apparently being in your 30s is like being a tween — you’re too old or too young for everything. YA has boomed so much in the past decade or so that we’ve seen it (and, correspondingly, middle grade) age up quite a lot, due in no small part to how many adults now read it. I don’t think that’s a net positive. (It’s why New Adult was supposed to come into being, but that failed, and that’s a different essay.) We adults, even if we think we’re relatively young, should not be Ugly Grownups, arrogant to the extent that we assume all of teen culture should be appealing and accessible to us. I co-host Hey YA right here at Book Riot, and I work with young adult literature in all sorts of other ways, too. There are so many things I love about YA, and one of them is how much richer and more diverse it is these days compared to When I Was Young and the many ways I can access, indulge, or soothe my teen self. But more and more, I find myself hesitant when writing reviews of books where I want to criticize something that feels implausible, because I no longer have a handle on what is “realistic” and what is not. What is improbable and what is quintessentially teen, just now teen, not then? Am I uncomfortable with this or that portrayal because it’s genuinely not good, or am I just no longer hip? My expectations are, I’m starting to think, probably unrealistic, and that’s on me, not on teens, to put in check. I’m trying to follow teens on social media, read their writing, immerse myself in their world insofar as I am welcome, but YA is not written for me, it’s written for them. As an adult I am, thankfully, welcome to this party, but its job is not to appeal to me or reflect me. I am a visitor. Adult writers of YA must put in the creative and research work to make sure they are reaching teens today, not their adult peers, and adult readers have to be willing to put in the intellectual and introspective work to consider whether our responses and critiques are really about the work in our hands or if they’re about us. YA realism is no longer something I can read and expect to see myself mirrored. It’s become a window. I’m going to have to be okay with that.