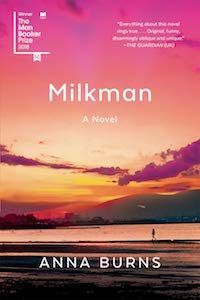

As far as I know, And Other Stories were the only publishing house to take Shamsie up on her challenge. I worked at this small, independent press in the north of England for the best part of a year. Their origin story was the first thing to draw me in, but I was also intrigued by their decision to partake in #YPW2018. More importantly, to be the only ones to partake in it. Like many publishing houses, And Other Stories were guilty of having more male authors on their list than female authors. But unlike many publishing houses, they acknowledged this and used Shamsie’s challenge to address it. In 2018 they published ten books by ten female authors, nine of whom were new authors for them. And many of the new authors have more books in the works. At the time of writing this, they have an equal number of male and female authors on the books. They are one of the few houses that do. What’s more, publishing women writers pays off (as we all knew it would). Dear Evelyn by Kathy Page won the 2018 Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, People in the Room by Norah Lange (translated by Charlotte Whittle) has been longlisted for the 2019 Best Translated Book Awards and The Remainder by Alia Trabucco Zerán (translated by Sophie Hughes) has been shortlisted for the 2019 Man Booker International Prize. Shamsie faces a lot of opposition, both for her critique of gender distribution in the publishing industry and her solution. Lionel Shriver, for one, does not see the point in publishing only women and deems it “problematic.” Ironically, Shriver is probably one of those people in the back that Shamsie needs to speak louder for. Shamsie is critical of the way in which the Women’s Prize for Fiction is viewed with less prestige than the Booker Prize. The Women’s prize (formerly the Orange Prize) was created to challenge the heavy male-centeredness of the Booker and prove that women are talented writers too. Yet Shriver, a winner of the Women’s Prize, has openly stated that winning the Booker would mean more to her. Missing the point entirely. I, too, questioned the usefulness of Shamsie’s challenge. Would a year of publishing only women really amount to much? At the end of her talk, Shamsie speaks of what 2019 might look like following a hypothetical 2018 of publishing only women. Her main concern is that the publishing industry doesn’t just resort to its old ways but continues to experience change. Despite the fact that the challenge wasn’t taken up with vigour, I do think having the conversation is beginning to spark change. Shriver may not have won a Booker Prize, but the winner of the Man Booker last year was a women: Anna Burns for her incredible novel Milkman. Two out of the five winners of the 2018 National Book Awards were women and five out of the six shortlisted books for the 2019 Man Booker International are by women (and all six are translated by women). Regardless of the verbal response to Shamsie’s challenge, last year showed signs that the publishing industry is taking better note of how talented female authors are. It’s no coincidence that the publishing community views the genres that tend to be female author heavy, such as romance and YA, with less prestigious standing. It’s also not uncommon for a book written by a man to be classed as “literary” when it’s a (very problematic) romance (Love in the Time of Cholera anyone?). But hopefully this is the beginning of such things changing. Shamsie’s challenged may have been a drastic solution to the problem, but she and many others have had the wherewithal to keep this conversation going until we see some change. I believe change is coming and are beginning to see the fruits of it. Just like Shamsie, I hope it continues.