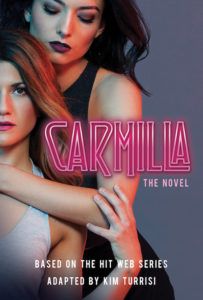

An adaptation of Shaftesbury’s award-winning, groundbreaking queer vampire web series of the same name, Carmilla mixes the camp of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the snark of Veronica Mars, and the mysterious atmosphere of Welcome to Nightvale. I recently read Deborah Harkness’s All Souls Trilogy. One of the story’s main characters, and the protagonist’s love interest, is the vampire Matthew Clairmont. I won’t go into detail about his complicated (fictional) life. Let’s just say that throughout the centuries, he has known some of the greatest minds in history, is now a professor of biochemistry at Oxford, and has attained a lot of wealth (aside from his family’s which is a different story). That’s pretty impressive, though it makes sense. If I had forever, I would probably (eventually) make a good use of my time. Wouldn’t you? Just think about all the books you can read! But I digress… I found myself enjoying the characters Harkness creates, because they are complex and flawed. I also appreciated the mythology she builds. But immersing myself in said mythology also got me thinking. Vampires are among the more popular, “cool” creatures today. They haven’t always been so, and their evolution is pretty interesting. In fact, originally they resembled zombies. As Paul Barber describes it in the introduction to his book, Vampires, Burial, and Death: Folklore and Reality: “If a typical vampire of folklore, not fiction, were to come to your house this Halloween, you might open the door to encounter a plump Slavic fellow with long fingernails and a stubbly beard, his mouth and left eye open, his face ruddy and swollen. He wears informal attire—in fact, a linen shroud—and he looks for all the world like a disheveled peasant. If you did not recognize him, it is because you expected—as would most people today—a tall, elegant gentleman in a black cloak. But that would be the vampire of fiction, a figure derived from the vampires of folklore but now bearing a precious little resemblance to them.” To be fair, I don’t think that most people would expect a gentleman in a cloak. They would probably expect either an attractive modern guy whose looks betray little or nothing about his true nature, or a beautiful and formidable woman. So how did we get from that

via GIPHY to this?

via GIPHY Essentially, it comes down down to three 19th century works: The Vampyre by John Polidori (1819), Carmilla by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu (1872), and—you guessed it—Bram Stocker’s Dracula (1897). In his article Vampire’s rebirth, Sam George outlines the circumstances in which Polidori’s story was conceived. Hint: Lord Byron had something to do with it. It appears that this tale was originated at the fateful gathering at Byron’s Villa Diodati, which is famous for being the source of inspiration for Frankenstein. The more I learn about that gathering, the more I wish I could attend. How awesome is it that one gathering resulted in the inspiration for two of the most iconic horror creatures?

via GIPHY Even though nowadays few people know of Polidori, in 1819 his story enjoyed great popularity. It also changed the image of the vampire from what was essentially a zombie that drank blood instead of eating brains to a mysterious, cunning figure. I am not sure whether Le Fanu and Stoker encountered it. They published their own works decades later. Still, it is possible that they might have known of it, given that they continued in its tradition. Both Carmilla and Dracula, like Polidori’s Lord Ruthven, are able to blend into society and prey upon unsuspecting female victims. (If you are interested in Carmilla and its similarities/differences with Dracula, Rioter Mary Kay McBrayer’s article on the topic is a good place to start.) At this stage, vampires are a lot more human, but they are still monsters or other. They have no qualms about victimizing innocent people and, therefore, ought to be stopped. This is they way they appear in numerous films and works of fiction. In the latter half of the 20th century, their image changed once again. This time, they were subject to series of novels such as Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles and L.A. Banks’s The Vampire Huntress Legend series. The latter is particularly notable, because Banks is one of the few authors of color to write on the subject (another notable work is Octavia E. Butler’s Fledgling). Series such as Banks’s and Rice’s made vampires much more complex. By the time Stephenie Meyer entered the scene with Twilight in the early 2000s, vampires were practically superhuman, with societies of their own and nuanced personalities that went beyond simply wanting to feast upon innocent damsels. The point is, in the space of two centuries, vampires went from folklore-based zombies to attractive Oxford professors. There is a lot to be said as to why this transformation took place, and Rioter Jessica Yang discusses this at length. But I think that ultimately, as society changes, so does the role of monsters in it. The folkloric vampire was a scary story which dealt with death and warned caution. The 19th century Gothic and Victorian vampire was another cautionary tale—the mysterious outsider/foreigner, the attractive stranger. Today, vampires are superhumans who do not have to fear death and who need very little self-care to be fully functional. They are still other, but much less so than before, and have skills and knowledge that is enviable and coveted.