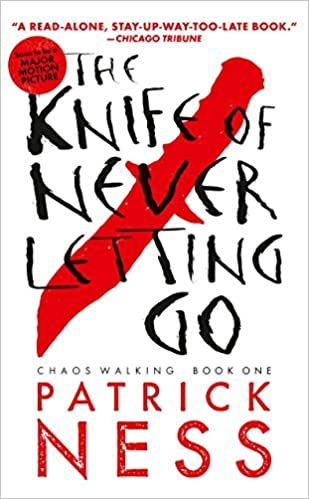

Most of us who consider “loving books” to be a part of our personality very likely got our start at a young age, devouring picture books and then slim chapter volumes. Many of the stories we read as children were bloodless, in the tradition of L. Frank Baum, whose Oz books were written to provide young readers with an alternative to the goriness of ancient children’s stories full of lopped off toes (Cinderella) and briars full of dead princes (Sleeping Beauty). Since the early 1900s, two things have happened that have substantially changed the way Western readers relate to death: our access to clean water and living conditions has vastly improved, as has our access to medical treatments that actually work (although in both cases, we still have a long way to go). This has relegated our experiences with death largely to books and film — whether fictional or on the 24-hour news cycle. It is also rarer to see a body on the news than in a movie, which makes sense. If it’s a movie, we know the body isn’t really a body, but a living person who will get up and walk away. It’s not real death. And yet, there are two things we can be certain of in life: that it will change, and that we will die. If we are lucky enough to have pets in our lives, we will very likely experience the trauma of their death as well. Pets, to quote my uncle when my beloved kitty died in 2019, are born to break your heart when they go. Animals are our companions, and losing them is somehow a more distilled experience than losing another human. That is to say: we keep our pets and do the absolute best we can for them. We love them fiercely, and they ask nothing of us in return except to be fed, loved, and played with. When we lose them, the grief is uncomplicated. In books, the death of an animal is often a hugely traumatic event for the reader. In Old Yeller, a beloved dog must be put down after saving his human family’s life. This one was made even more pathetic (in the pathos sense of the word) when it was turned into a movie in 1957. The lesson of Old Yeller is that sometimes, no matter how much we love a thing, we must let it go. It is a brutally painful lesson, and one that we all learn at one time or another. In this spirit, Old Yeller presented readers in the 1950s with a taste of what that feels like, either in order to empathize with those who have already learned the lesson, or to prepare those who have not. In The Knife of Never Letting Go, the dog’s death occurs about halfway through the story, which changes the lesson a bit. Tom’s canine buddy, Manchee, is left behind to save Tom and his traveling companion, Viola, from a violent preacher who is chasing them. In this world, men can hear the thoughts of others — including animals — so Manchee’s sacrifice for Tom is a choice, and his murder at the hands of Aaron hits the reader right in the chest. But this plot device is more than just a manipulation on the part of the author; it serves as a clear indicator that Aaron is murderously deranged to the point of harming not just his fellow man, but animals. The death of an animal here illustrates a kind of depravity that is frightening because animals are innocent of human motivation. Pets in books also mark an epoch of life. In Marley & Me, the titular Marley is a terror disguised as a yellow lab who simply cannot comprehend what his humans want. And yet, his clear love for his humans, as well as their growing understanding of him, forms the backdrop for the autobiographical story. When Marley dies at age 13, the baker’s dozen years that the author and his family had with him are brought into perspective, and the real lesson is what everyone learned about themselves along the way. Nothing in fiction is accidental, especially the death of a character. All the animals who died in the texts I mention are dogs, which are a long-standing symbol of fidelity in almost every culture; dogs are man’s best friend, after all. But regardless of species, the death or pain of an animal in a book is meant to signal something to the reader. Our quest as readers is to process the pain of that loss and then seek out the reason the author has taken us on that particular journey. Whether we decide to accept that quest or not is an individual choice and dependent on our emotional and mental state at the time. When the movie adaptation of Marley & Me came out in 2008, I clearly recall walking by a movie poster at a bus stop that had been enhanced with “the dog dies!!” in Sharpie. I’m forever grateful to the Sharpie-wielding vandal who marked up that poster, despite my hatred of spoilers; I’m not a person who feels catharsis after these kinds of experiences, so I was able to avoid the movie all together. And in the end, that is what I wish for you as a reader: the ability to choose whether you can handle the impact of this kind of plot point.