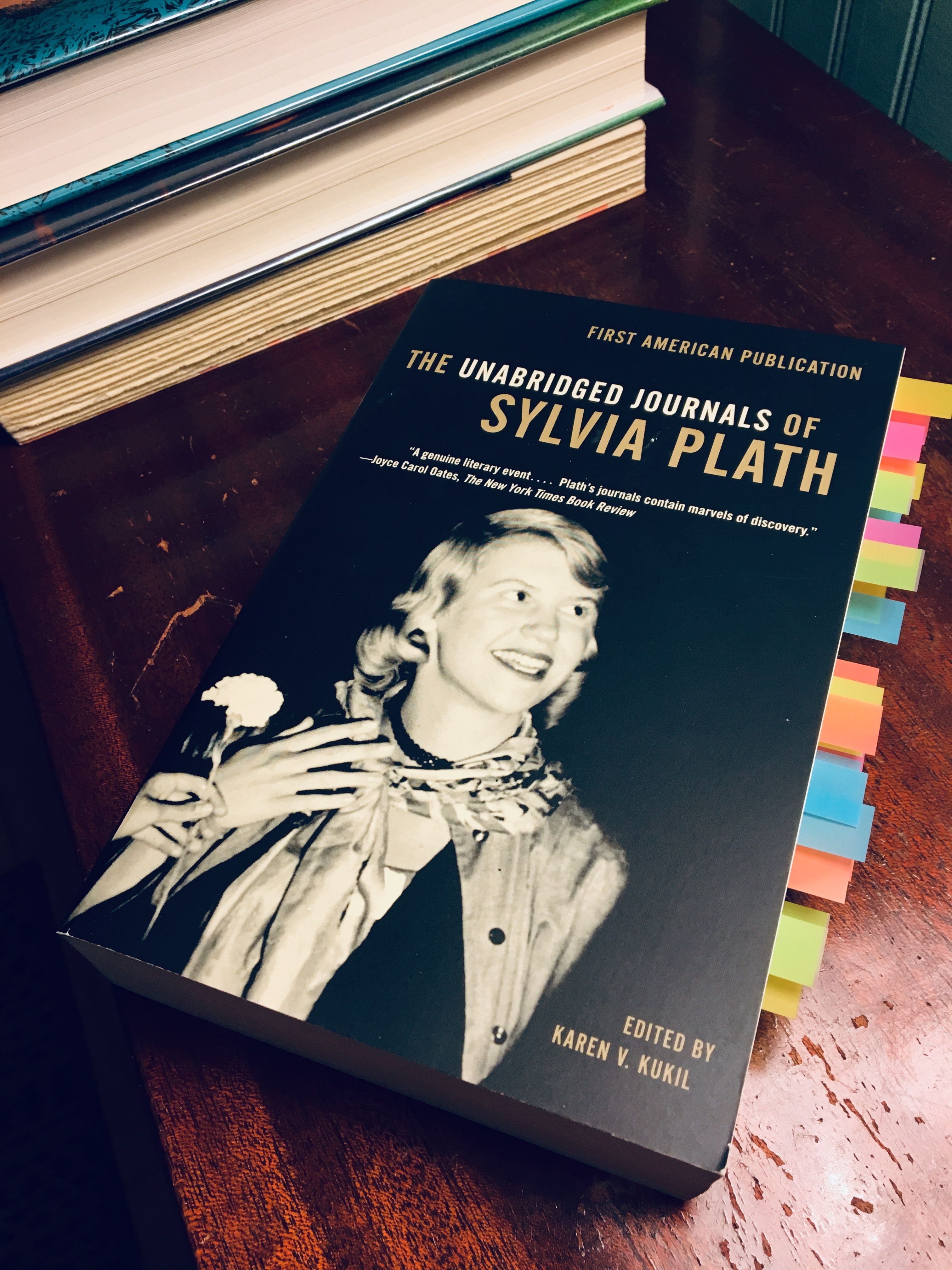

I bought my own copy of her Unabridged Journals, and my own copy of her Collected Poems. I had read parts of both, but neither in completion. For the longest time, they sat untouched in a corner of my living room, with their mere presence making me feel comforted. I knew Sylvia and her words were in the room with me, even if I never touched them. But I soon learned that I needed to confront my feelings—I needed to confront the past in order to gracefully enter the future. I knew I finally needed to read the Unabridged Journals cover to cover. When I first read parts of Plath’s Collected Poems from the library in high school, based on a recommendation from a favorite English teacher, I could never articulate why her words resonated with me so much. I just knew they touched me and made me feel safe. When Sylvia and I met again in college, I still couldn’t put my finger on why she meant so much to me. It was only when I first started reading the Unabridged Journals later that year, stuck in my own personal bell jar of anxiety, depression, and feeling lost, did I begin to realize where the connection was coming from. Sylvia, like me, felt crushed under the weight of age-old expectations of adulthood. Sylvia, like me, did not understand why she had been steeped in the make-believe of fairytales when real life felt nothing like it. Sylvia, like me, did not understand how she was supposed to summon a level of confidence that was nonexistent to pursue her writing dreams, let alone to be a functioning adult human being. Sylvia Plath, like me, was depressed for a very long time. And since neither of us really knew how to handle it, we handled it with each other. It took me a long time to realize that there are some people who actually grow up feeling reasonably content with themselves. I, on the other hand, was obsessed with perfection and control from a young age. As I grew higher, so did the pressure. I was anxious. Then I was depressed. I was lost in an endless twister of anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder for many years. Not once did I ever think that what I was doing to ensure everything would be fine was actually causing the problems. Not once did I ever believe I could stop being so hard on myself. Not once could I ever believe that life wouldn’t be this hard and good things would happen. Being young is hard, especially when everyone matures at different rates. The age you are and the age you feel are two different things. At 18 or 19, keeping up a facade that said I wasn’t being crushed under the weight of becoming a person was exhausting. But when I read Sylvia Plath, I knew I didn’t have to keep up that facade. She knew and understood what I was going through. I didn’t have to pretend. But I was also distracting myself instead of confronting myself. I might have related to Sylvia’s words, but I still couldn’t accept the reasons why. I couldn’t accept that I was scared of uncertainty to the point of believing anxious rituals would control the outcome of things. It took a long period of self-reflection to finally begin letting those things go, during which I wasn’t turning to Sylvia. I had only myself to turn to, as it should’ve been all along. “But I am foundering in relativity again. Unsure. And it is damn uncomfortable,” she writes in the Unabridged Journals. Accepting that life is uncertain and we have no control over it is very damn uncomfortable. But it’s easier to live a life of foundering in relativity than to spend your entire life trying to escape it. I don’t think Sylvia Plath was ever able to find the place of inner peace that I was able to find, but I’m still grateful she was there with me. There for the darkness, and there for the light.