The Harlem Renaissance included a rich array of publications called “little magazines.” These literary journals could be compared to the ‘zine movement of the late twentieth century—the little magazines allowed space for not just poetry and prose, but also for essays of radicalism, of experimental writing, and for space for subversion. Many of the magazines included critiques of not just the established (read: white) culture, but they also were unafraid to comment upon the work of other black leaders. Little magazines were founded by individuals or small groups of creatives, and they were bastions of independence from the established literary culture. One of the cornerstones of the little magazines of the Harlem Renaissance was their focus on publishing new and little known voices, right alongside some of the powerhouses of black literature. The magazines were primarily distributed locally, though some had a more national reach; this, of course, influenced the voices and perspectives presented and the intended audiences for the magazines.

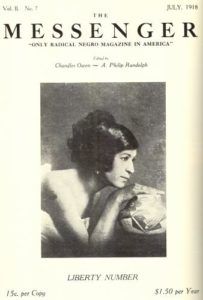

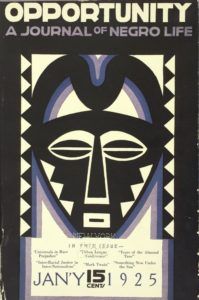

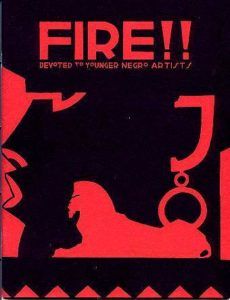

The Harlem Renaissance emerged at the same time as the modernism movement in American literary history, and many of the discussions that occurred within the modernist movement were mirrored in not just the Harlem Renaissance movement but also within their little magazines. Many felt the magazines should take a political stance. Others, however, felt they should be forums to allow art to stand for art’s sake. Even reading through the journals, one sees these divides—a reminder that, despite being part of a flourishing and historically significant movement, no movement is a monolith. It’s nuanced, it’s complicated, and it’s what makes literary history and the growth of powerful writing endure. Little magazines, as vital as they were to the Harlem Renaissance and literary history, are exceedingly hard to track down, and because they had such short runs and were spearheaded by a single or small group of individuals, very few still survive. More, many are likely not even known to us today. One of the first little magazines was The Messenger, founded by Chandler Owen and A. Philip Randolph in 1917, a black writer and black Civil Rights leader respectively. Originally a magazine with a deep socialist bent, as the 1920s began, it began to publish more black creatives, helping really give a space for discussing and developing black intellectual, political, and creative culture. The Messenger, though it was centered in Harlem, eventually found itself publishing and reaching black creatives throughout the U.S., and they often ran essays about the burgeoning middle class blacks across the country, highlighting their wide ranging successes. Most little magazines kept their reach more locally. Perhaps what The Messenger was known for most was their movement to end the political career of—and indeed, deport—Marcus Garvey. You can read reprints of some of the issues of The Messenger via the Haiti Trust Digital Library. Journalist and abolitionist W.E.B. DuBois played a significant role in the history of Harlem Renaissance little magazines. DuBois launched a number of platforms for himself and his writing prior to the 1920s, and it was during the Renaissance when he become a patron for many journals. His influence was felt in The Crisis, which was one of the biggest magazines of the time. Many of the contributors had been patronized by DuBois, and could therefore have their voices heard more widely. Interestingly, as the 1920s growth of little magazines continued, DuBois and his influence on both the little magazines and on black writers waned; this was due to the rift in writers between the belief that art exist for art’s sake and art existing for the sake of political statement. Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life started in 1923 and was founded by the National Urban League as a journal to highlight the literary culture of the Harlem Renaissance. The journal focused on advancing opportunities in all aspects of life (career, education, opportunity) for black people. Although many of the little magazines at the time had essays and critiques of modern practices and rhetoric, Opportunity offered up data and research relating to black lives in America. This practice, as well as its editorial angle toward the middle class, for many, made the magazine feel like it was meant to appeal more to a white audience than to a primarily black one. That the magazine had been partially financed and supported in its renaissance by Ruth Standish Baldwin, a white lady, furthered this perception. The journal published many outstanding voices of the Harlem Renaissance, as much of its early run offered a forum for literary endeavors. Some of the writers included Countee Cullen, Gwendolyn B. Bennett, and Langston Hughes. Opportunity isn’t readily available online, but archives of the magazine exist in a number of college and university libraries for perusal, most likely in scanned microfilm or fiche versions. Fire!!, which made its debut—and indeed, its only appearance—in 1926, was one of the little magazines which had a slate of impressive literary talent behind it. Founded by Wallace Thurman, Langston Hughes, Aaron Douglas, Bruce Nugent, Gwendolyn Bennett and John P. Davis, the magazine was utterly radical for its time, even among a culture of radical black activism and creativity. Fire!! struggled financially from the beginning and took an even bigger hit when the offices for the magazine burned down shortly after its publication. The magazine gave space for fiction and essays and opened its spaces to talking about topics like homosexuality, bisexuality, prostitution, colorism, and more. One of the big challenges during the Harlem Renaissance, which played out through its little magazines and other creative ventures, was the varying beliefs among black leaders about the best way forward. Indeed, the Harlem Renaissance’s time frame places it post-slavery, during the Jim Crow era, and deep in the era of the Great Migration. Fire!! was one magazine some felt held back progress for the black community, while others saw it as a necessary, indeed subversive, means of claiming their own space. More, it was independent and didn’t depend upon patrons or a mother company. Fire!! can be read in full thanks to the POC Zine Project online, but you can also pick up a reproduction print of the magazine, too. There’s also a fantastic and more in-depth history of Fire!! at FIYAH: Magazine of Black Speculative Fiction and how the little magazine influenced the contemporary title. Other magazines that played a significant role in the growth of black writers of the Harlem Renaissance included Crisis, which got its start in the early 1900s and served as the journal for the NAACP; Stylus, which began as a student literary journal at Howard University (an HBCU) and featured the work of then-student Zora Neale Hurston; Harlem, which published one edition under the eye of Fire!! founder Wallace Thurman in the late 1920s; and many, many more. This is a taste of the rich history of little magazines in the Harlem Renaissance. For a bit of a deeper dive with an academic spin, check out “Forgotten Pages: Black Literary Magazines of the 1920s” from the Journal of American Studies, Volume 8, Number 3, December 1974, by Abby Ann Arthur Johnson and Ronald M. Johnson of Howard University. You can access the article for free via JSTOR (you may need to register). Want more books about black history and by black authors? Check out these 25 children’s books for black history month, black comics by black artists, and these books by black authors that should be on everyone’s bookshelves.