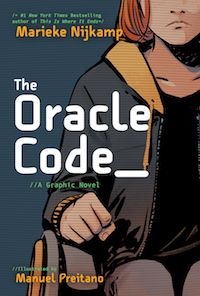

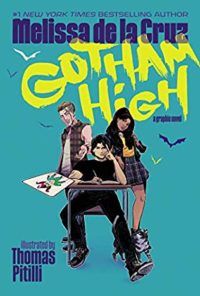

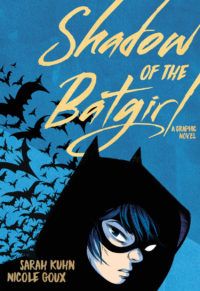

Our reptile brains are, however, constantly at odds with our logic circuits, the latter of which very much enjoy categorizing things; doing so calms our fears and anxieties, stabilizes past, present, and future. It allows us to assign rational explanations to events like war and climate change that would otherwise be incomprehensible. It allows us to slot everything neatly into a larger picture that’s (relatively) predictable and (mostly) makes sense. This tendency extends not only to everything around us but also to what’s inside of us, including our emotions which we toss into either “good” or “bad” baskets. That does a disservice both to our emotions and to us because, like magic, it isn’t the thing itself that’s positive or negative. It’s what we do with the impulse that matters, but again, human nature demands simplicity and order. I’ve been thinking about the anger = bad theorem in general a lot lately and specifically as it applies to Cassandra Cain in Sarah Kuhn and Nicole Goux’s Shadow of the Batgirl, Barbara Gordon in Marieke Nijkamp and Manuel Preitano’s The Oracle Code, and Selina Kyle (and Bruce Wayne and Jack Napier) in Melissa de la Cruz and Thomas Pitelli’s Gotham High. As a species, not only do we tend to shy away from emotions that live in the “bad” basket but, when we’re forced to confront them, our immediate reaction is to feel uncomfortable. Which, again, is counterintuitive since we’re born with the chemicals to trigger the feeling and the receptors to translate the mix. Our brains and their component parts, it would seem, agree with Nijkamp, who pointed out during a recent roundtable discussion with the three aforementioned authors, “We would all do so much better if we were more comfortable with being uncomfortable.” Because it makes us uncomfortable, society has a tendency to tell people of all ages, especially women and girls, that not only is anger something we shouldn’t express, but something we shouldn’t feel. This is even more true of marginalized characters, Kuhn reminded us, including those who are disabled characters like Barbara Gordon, and “Women of color (Selina), Asian American women (Cass) who aren’t really given space to have those feelings or to show those feelings or to sit with them for a while so it was important for me to show that as well. You can take that space, you should take that space and if the people around you care about you, they’ll let you take that space and help you in that process.” Shadow of the Batgirl, The Oracle Code, and Gotham High are very different books (remember, comics are a medium that can be used to tell stories of any genre) but they share a very important theme: the transformative power of anger. Each of the POV characters in the graphic novels is facing a difficult situation in their respective narratives: Cass has run away from the father who raised her as a weapon, isolating her from human contact; Barbara has been paralyzed by a stray bullet. Selina is caring for a parent with a chronic illness. Bruce has lost his parents to tragedy. Jack lives in not only financial poverty but emotional poverty as well. They all have reasons, beyond what de la Cruz describes as the normal teenage anger at the realization that “‘The world sucks!’ They’re angry they’ve been lied to, the film is coming off their eyes’” to feel anger. If they were living in the real world, we’d tell Cass, Babs, Selina, Bruce, and Jack to calm down. To get over it or move past it. We’d try to be compassionate (I hope) but most of us would recommend a school counselor or therapist and then back away slowly. The trusted adults and friends who populate these books don’t do that. They don’t hide. They don’t redirect. They don’t ever suggest that kids and teens should stomp their emotions down and forget about them or temper them. Whether gently or openly, slowly or outright, they accept. They listen. And then they help Cass, Babs, Selina, and Bruce (poor Jack) figure out how best to express that anger, how to use it to accomplish something. They live by the maxim, to quote the West African spider god as portrayed by Orlando Jones, “Anger gets shit done.” Cass is angry. She learns to be human. Babs is angry . She learns how to find herself. Selina is angry. She learns how to make her own life. Bruce is angry. He learns how to make his own family. Jack is angry. He learns how to survive. We may not always agree with the method or outcome a given character chooses (spoilers, darlings) but we can’t deny that, by the end of the Shadow of the Batgirl, The Oracle Code, and Gotham High, each is transformed. They are something more than they were before not despite their anger but because of it. Which means there are two lessons here: the first is that not only is it okay to be angry, it’s okay to express that anger so long as you’re doing it in a way that doesn’t hurt anyone. The second is that, as trusted adults (and co-readers), we need to learn to not only allow but encourage the children and teens in our care to tell us when they’re angry, to give them the space to feel those feelings, to express them to us, and to help them figure out how best to utilize those energies.