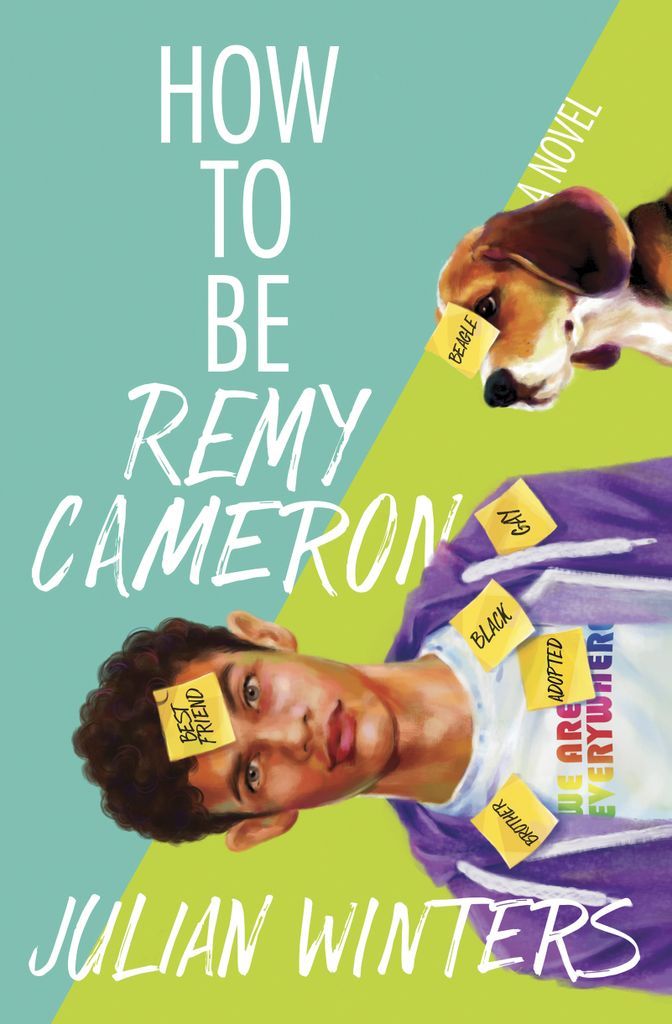

Everyone on campus knows Remy Cameron. He’s the out-and-proud, super-likable guy who friends, faculty, and fellow students alike admire for his cheerful confidence. The only person who isn’t entirely sure about Remy Cameron is Remy himself. Under pressure to write an A+ essay defining who he is and who he wants to be, Remy embarks on an emotional journey toward reconciling the outward labels people attach to him with the real Remy Cameron within.

Read an Excerpt from How to be Remy Cameron

Ms. Amos is leaning against her desk. Her mouth is twisted into a dramatic smile, one far too smug for any high school teacher. It’s unfair. With the swipe of her red pen, she can change our academic futures—seriously, it’s probably one of those inexpensive ones from Target. She shouldn’t be given the right to torture us with silence and deep stares and awkwardness at the beginning of class. “I’ve made a decision,” she finally says. Someone mumbles, “Retirement,” coughing into his hand. No one laughs. Andrew Cowen is a senior, Brook’s teammate, and hosts the ghost of a failed sitcom-dad in his scrawny, six-foot body. He and Ford share a special throne in Douchebag Hell. “I guess you’ll find out next year when you repeat my class, Mr. Cowen?” retorts Ms. Amos. Andrew slumping in his chair only broadens Ms. Amos’s grin. “Thanks to Mr. Turner’s colorful excitement over tapping into the works of Tennessee Williams, I’ve decided to move up an assignment I was saving for after the Thanksgiving break.” A symphony of sighs and groans unites everyone, including me. Screw you, Ford Turner. “Please.” Ms. Amos cocks a hip and winks. “Contain your glee.” I thump my forehead against my notebook. Jesus. The last thing I need is more work in a class I’m barely passing. “You’ll be composing an essay. A very personal essay.” Ms. Amos crosses to the other side of the room. “The subject is simple: ‘Who am I?’ Write a thought-provoking—and, yes, I realize that’ll be terribly hard for you, Mr. Turner—essay about who you are. What defines you?” Ford sniffs, chin cocked. Ms. Amos walks back to her desk. “Are you defined by your race? Religion? By your music tastes?” A student with a choppy haircut and a questionable face-piercing throws up devil horns and starts headbanging. Behind me, Chloe snorts. “Are you defined by your privilege?” Ms. Amos stops in front of Ford’s desk. “Since I’m privileged enough to take your class, I guess not,” replies Ford. Jocks in a row at the back of the class chuckle. Ms. Amos ignores them and steps over to Chloe’s desk. “Are you defined by your strength?” Then, to Sara, “Are you defined by your family’s history? Your clothes?” A painful lurch, like the aftershock of an earthquake, moves through my chest when Ms. Amos stops at my desk. “By your name?” To the room, she asks, “By your sexuality?” From the back of the class, a jock says, “Well, Remy might be.” How very unoriginal. It’s as if I can see these things coming, these ridiculous, homophobic jokes that I know will always follow me. But I can’t ever predict how my body will react. Will I tighten up in anger? Will I freeze up in fear? Will I blush with embarrassment? Ms. Amos, unentertained, folds her arms across her chest. “Are you defined by how many days you’ll spend reviewing your life choices after being expelled for bullying? You remember our Zero Tolerance policy, correct, Terrance?” Silence blankets the room. If only it was quieter behind my ribs. “Take this assignment seriously. It’s worth thirty percent of your grade,” Ms. Amos announces. “That’s basically pass or fail,” Ford says, choking, as his freckled face went blotchy red. Ms. Amos nods; the corners of her mouth curl more deeply. “All essays must be typed, double-spaced, and submitted to me the week before Thanksgiving break.” She’s back at her desk, leaning. She’s short, five-foot-nothing; her feet swing and the toes of her shoes skim the floor. “Also, there’ll be oral presentations of your essays.” In my peripheral vision, I spot Ford discreetly poking his tongue into his cheek. Of course. The asshole is imitating a blowjob. Talent like that will look good on his college applications. Behind him, Ryo Itō hisses, “Knock it off.” Ford sniffs. Ryo gives me a small shrug. He’s a senior and super popular in the gamer crowd. I suck at video games; I’ve got no true hand-eye coordination skills. But Ryo and I have a silent respect for each other. We share a singular passion: disdain for bottom-feeders like Ford. “You can use any art medium you want for presentations. Music. Photographs. Visual media, PowerPoint, whatever.” Ms. Amos’s relaxed shoulders expand. Pointedly, she says, “Help us understand who you are.” The class mumbles and nods. A few students are furiously taking notes. Sara’s rubbing her temples. Yeah, my brain is ready to skydive right out of my skull. When Ms. Amos returns to rambling about Tennessee Williams, I slump so far down in my chair, I nearly split my chin on the desk. This. Is. Perfect. An entire essay on who I am. Essays aren’t among my favorites. I was banking on studying extremely hard for the final exam to pass this class. I need this class to boost my application for Emory. Average student and GSA President aren’t enough. AP literature is my golden ticket. Ms. Amos’s affiliation to Emory is the key that unlocks the gates. But an essay that determines my final grade? I’m freaking doomed. After school, Maplewood High’s student parking lot is like a scene out of an apocalyptic film, one of those gorgeously-shot movies starring kids from Disney Channel spinoffs. The suburbs of Dunwoody are too pretty for George Miller-style adaptations. Tucked under a blanket of pale blue sky, the gray of the parking lot is broken up by bright yellow parking lines and sparse clumps of green grass that lead to the woods nearby. The only cars left belong to sporty students or band geeks or detention-dwellers—and slackers like me. Curbside, Lucy’s next to me; our asses are numb from sitting so long. The late afternoon sun stretches its golden paws over the far side of the cracked pavement. The sweet afterglow of midday heat lingers. Georgia in the fall is a different kind of beast. It’s humid and thick and sweaty as if it were still June, and at the same time the air still tastes a little like September: sweet-tart McIntosh apples and spicy butternut squash. As if reading my mind, Lucy says, “The Gwinnett County Fair.” I smile and hum. We share a look that says we already miss sharing funnel cakes with Rio, with our mouths covered in powdered sugar, in a cool September evening. In the distance, I can hear the marching band: snare drums and trumpets and that swell from the brass section. They’re trying something new, a cover of a Gorillaz song. It’s sick. My foot taps against the ground with the drumline. The first big pep rally of the year is Friday. My anticipation is high. Sneakers pound against the ground. The cross-country team trots by. They all wear tiny athletic shorts and loose shirts. I hide my grin in the crook of my elbow. Some of the guys are just—I don’t know—something about sweaty hair and tinted cheeks, focused eyes and syncopated breaths. I cross my legs, hoping no one notices the little twitch in my jeans. Lucy whistles. “Hot.” Infinitely embarrassed, I elbow her. “You don’t think so?” “What? No.” “Liar.” “Whatever,” I mumble, shaking my head. Lucy returns to coloring the toe of her Converse with a red Sharpie. My phone sits on the sliver of asphalt between us. I have one earbud in. POP ETC pumps into my veins. “Backwards World” comes on and I think, How appropriate. Across the lawn, to our left, I spot Silver ducking behind the main building. No doubt he’s headed to have a cigarette out of teachers’ view. Silver is a mystery, an undiscovered planet. He’s a quiet loner, unlike his older sister, Darcy, who is Maplewood High’s resident religious dictator. Popular and sparkly and influential, she’s president of the Godly Teens First Organization. Yep, GTFO. I don’t know why no one’s voted that name off the island yet. Silver’s real name isn’t Silver. It’s a nickname other kids gave him for his pale-blond hair, stormy eyes, and nimbus-cloud skin tone. I’ve never said much to him though we’re both juniors. Something about Silver seems untouchable. Students adore him for his looks but fear him for his silence. Watching Lucy from the corner of my vision, I bite my thumbnail. “What do you wanna be when you grow up?” I hate that phrase: “When you grow up.” I’m seventeen, a quarter-inch short of six-foot-one and have a long-standing love affair with cold brewed coffee. I’m probably not growing anymore, not physically. I’m cool with that. But Ms. Amos’s essay has me on edge. “Grow up?” “Yeah. Grow up,” I repeat. Lucy’s lips twist into a smile. “You mean once you get past this immature dickhead phase.” “Is it really a phase, Lucia?” I tease. Despite the dark curtain of inky-black hair falling below her brow, I can still see Lucy roll her eyes. “I don’t know. You first.” “An actor.” I reply with the conviction of a true thespian—which means none at all. “You definitely have the dramatic part down.” “Hey!” I nudge her shoulder until Lucy almost tips over laughing. “We both know your dream is to go to Emory and become some world-famous writer.” I nod, but my stomach twists into eighteen knots. I’ll never make it to Emory without this essay. I did a little research after the AP Lit class: part of the admissions requirement is an essay, a personal statement. They want to know who you are. So freaking perfect. “Don’t you ever think about these things?” I ask. Lucy’s shoulders pull tightly when she’s shrugs. It’s the first sign. “Sometimes.” A lie. Lucy’s a thinker and a planner. “I wonder if my dad imagined being a father at twenty-two. Did he want it? Or was it something he involuntarily settled into?” I nod, but she doesn’t see. Chin tucked, she’s glaring at her shoes. “A lot of adults do that—settle for what they become.” There are sad wrinkles beside her mouth. “They lose that thing you need to fight.” “What’s ‘that thing’ they lose?” Lucy shrugs again. She tips her head skyward. Floating islands of overcast clouds hide the sun. “Who knows, Rembrandt.” We sit in silence. The late school bus chugs in, its motor rattling. Detention-dwellers hop on like convicts minus the orange jumpsuits. Silver emerges from behind the school and pops the collar of his dark denim jacket. His profile is sharp: long, thin nose and photogenic cheekbones, downward tilt to his bitten-red lips. He was born for the runway. The marching band has quieted to just the woodwinds, a somber tune. I clear my throat. “I want to be a guy Willow looks up to. A role model. My little sister is all I have.” Lucy’s foot nudges mine. Her half smile is a reminder that Willow’s not all I have. “I want her to know she can be anything.” “Me too.” Lucy nods. “I want to make my sisters proud.” She’s the oldest of four girls. Her father stuck around long enough to realize he was settling, four daughters later. It’s weird—this bond Lucy and I have burrows deeper than liking the same movies or long hugs or laughing. We’re both children of abandonment, I guess. We don’t talk about that, but it’s there like the roots of a tree, like a sunrise. It’s there, even when people aren’t talking about it. We smile at each other. Maybe all of this is too heavy for today. “We should hit up Chick-Fil-A,” suggests Lucy. “Brook’s almost done with swim practice. I’m dying for an Arnold Palmer.” “Gross!” “Oh, come on,” Lucy says, tugging my right ear. “How long are you going to hold this vendetta against sweet tea?” It’s not a vendetta; it’s a lifelong commitment. Sweet tea is the devil’s juice. I know it’s a southern tradition, but it’s sadistic. Iced tea shouldn’t be sweetened. It shouldn’t even exist. The tangy-sugary mixture of sweet tea and lemonade to make an Arnold Palmer is against what I represent. “It’s downright disrespectful.” “Remy, seriously.” “It should be outlawed.” Lucy sighs. “We live in Georgia.” “Exactly! Everything should be made of peaches.” “There’s peach sweet tea.” I frown at the sky. “What has this world come to?” Lucy’s laughter is contagious and it infects me like a wild fever, shifting from my belly to my chest in hyperspeed. “Anyway, I can’t.” I reach for my phone. “I’m supposed to meet Mom and Willow.” A text notification from Mom awaits me. Underneath that is a Facebook reminder: Friend request from Free Williams. I forgot all about that. But I don’t have time. I swipe away the Facebook notification, already anticipating a lecture from Mom for being late. After dusting off my jeans, I help Lucy to her feet. “It’s cool. I’ll just hit Rio up,” she says. “We’ll grab milkshakes. She’s always down for those.” “Are you trying to make me jealous?” “Maybe.” Lucy grins as if the lie is puckering her lips. “Is it working?” “Hell yeah!” Lucy’s fingers wrap tightly around my elbow before we reach my car—full-on death grip. I wince, trying not to squeal like a trapped puppy. She’s pointing toward the doors outside the gym. I suck in a shallow breath. The universe truly loves me. Ian, shoulders pulled forward, chin lowered, eyes the ground while the swim coach talks to him. Coach Park, Ian’s dad, has been a staple at Maplewood High for a decade, continuously leading the team to championships or at least runner-up status. He’s quiet and stern and slightly intimidating. My eyes are drawn to Ian. He’s a spot of blue ink against a gray canvas. A prism of rainbow light in a sea of ordinary. A promise and a bad decision. “He’s cute,” whispers Lucy. “That likeable kind of weird.” I lick my suddenly dry lips. My heart twitches, then thumps, then turns into an entire drumline inside my ears. But I don’t know why. It’s just Ian. Of course, that’s not how my brain works, or my body. My fingers tingle, and my lips are itching to smile. On all future job applications, I think I’ll add ‘has zero chill when looking at cute, potentially dateable people’ under the Other Skills heading. “No new relationships, Lucia,” I remind her—and myself. “Are you remixing Drake?” I exhale dramatically. “Fine.” Lucy pouts. “Let that jerk-face Dimi ruin your future love life. Kill your barely-existent sex life in the process.” A sting of blush assaults my cheeks. I should’ve never told Rio or Lucy about losing my virginity: massive, unforgettable mistake. Not the sex part, though, that was—actually, I don’t want to think about that part. I don’t want to waste anymore brain cells on Dimitar Antov. “You can date again.” Lucy’s hand slides up to my shoulder, squeezes. “It’s legal.” A lump the size of Mars clogs my throat. “Yeah, whatever. I’m late.” I wave and jog to my car. I’m desperate to get away from conversations that lead nowhere, nowhere except frustrated sobbing and a playlist of tearjerkers and bad, acoustic cover bands. I don’t want to go there.