And then there’s the matter of money: no matter the history of a piece, someone will buy it, making art theft an attractive crime to commit. A few weeks ago, a man walked in to a gallery in San Francisco, took a Dali etching off the wall (the gallery doesn’t alarm its work), and departed with it. Whether or not he’ll be caught is questionable, despite the theft having been captured on security cameras, and despite photos of the piece being broadcast on the internet. The etching will turn up eventually, perhaps in a private collection, years from now, perhaps having been laundered and sold several times, and the thief likely long gone. Reading this saga reminded me of a book I read years ago about an infamous, still unsolved heist in Boston: The Gardener Heist: The True Story of the World’s Largest, Unsolved Art Heist. I’m sure you all know what happened next: the rabbit hole. This one let me in a different direction than that which I was expecting, however: rather than focusing exclusively on books about heists from museums, I ended up with a few of those and a pile of books about smuggling, international law, and repatriation rights, many of which read like the plot of an Indian Jones movie, except that instead of belonging in a museum, the artifact in question belongs to the nation and culture from which it was stolen. A note on diversity: art historical scholarship, even books about repatriation and criticisms of the manner in which museums handle acquisitions until just a few decades ago, is still a notoriously white field. Though women have become much more active in the last three decades, I wasn’t able to find many books by authors of color. The field will hopefully continue to evolve to include more opinions and points of view as more artifacts are returned the their nations of origin.

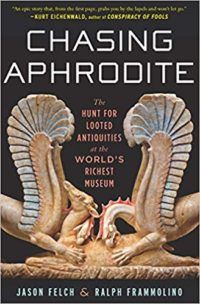

Chasing Aphrodite: The Hunt for Looted Antiquities at the World’s Richest Museum by Jason Felch and Ralph Frammolino

The J. Paul Getty Museum is the richest museum in the world due to the massive endowment left by its founder upon his death. When it was established in 1953, The Getty set out to be the premiere classics collection in the country: a challenge in the state considered a cultural wasteland by the great institutions of the Met and the Boston MFA. It’s interesting to note that Getty himself, who began collecting antiquities later in his life, refused pieces of dubious origin on several occasions but the museum that was his legacy had no such qualms. Until they got caught. The lengths curatorial and administrative staff went through to hide their shady dealings is impressive, but ultimately they were exposed and forced to return many of the stars of their collection. The story of how the pieces were traced is fascinating and this is one of those rare nonfiction books that keeps a conversational tone that invites both professional and lay readers into the story and holds them there.

Loot: The Battle Over Stolen Treasures of the Ancient World by Sharon Waxman

Who owns history? It would seem a complex question with a simple answer: no one. History is the past and anyone who wishes to explore it may do so freely. Art, and especially antiquities, however, are another matter entirely. Do they belong in museums where they can be conserved and seen by the greatest number of people? Or should they be housed in their country of origin, either in that nation’s institutions or in situ where they were found? Waxman explores these questions and others in Loot, tracing the implications of repatriation from the U.S. to Turkey, Egypt, Greece, and Italy, the nations who have been most vocal in their demands for the return of their heritage (and property).

Stealing Rembrandts: The Untold Stories of Notorious Art Heists by Anthony M. Amore and Tom Mashberg

According to Amore and Mashberg, galleries and museums lose $6 billion a year or more to art theft. Some of the most commonly targeted paintings, according to the security expert and investigative journalist, are Rembrandts. The master’s paintings have gone missing from institutions in Stockholm, Boston, Worchester, Ohio, and other locations, the thefts themselves ranging from walk-aways, like the Dali heist mentioned above, to violent confrontations. People are willing to die to get their hands on a Rembrandt. Why? Because, as also mentioned above, someone will always buy them, and these paintings—unlikely a $20k Dali etching—are worth millions and, provided they’re kept in good condition, continue to appreciate. Why Rembrandt in particular? You’ll have to read the book to find out.

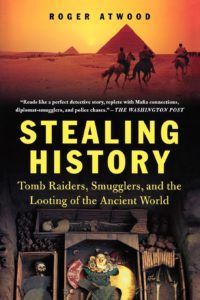

Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World by Roger Atwood

Greece, Italy, Turkey, and Egypt aren’t the only countries to have lost important pieces of their history to looters, smugglers, and museums. Peru, Cambodia, and Iraq have also been targets, and lest you think such activity was a thing of the past, Atwood reminds us that there was a massive spate of looting when Saddam Hussein took power in Iraq and then again following the 2003 invasion. Atwood also discusses how large shows at large museums can, themselves, incite looting: those who live in and around Sipán, Peru, began robbing graves with increased frequency after a show of artifacts garnered the attention of American collectors and the American press. It was a way for desperately poor people to feed their families while intermediaries got rich and museums added to their collections. So where we go from there?

The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War by Lynn H. Nicholas

The Nazi party was big on purging “degenerate” art. Individual Nazis, such as Hermann Goering, liked to go on “shopping sprees” through the grand galleries and private homes of Europe. The Allies worked against both to save works such as the Mona Lisa and The Rape of Europa. If this story sounds familiar, it’s because it was explored in 2014’s The Monuments Men. The salvation of these works isn’t all fairytale, though: while museums were often able to get the works stolen from them back, they also acquired new ones, many of those stolen from Jewish families and other private collectors who have since asked for their return. The museums, having bought the pieces, are reluctant to take losses. And to whom do works like The Rape of Europa actually belong? To the museum from which it was stolen by the Third Reich or to the country from which the museum sold it in the first place?

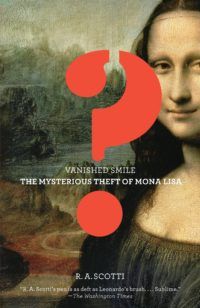

Vanished Smile: The Mysterious Theft of the Mona Lisa by R.A. Scotti

In 1911, the Mona Lisa disappeared from the Louvre. It took several days for anyone to notice: Louis Béroud, a painter who had been copying the work, returned to the museum on August 22 after an absence of a few days to find the great lady vanished. He informed security, who assumed the curatorial staff had taken her to be photographed, and thus no one was immediately alarmed. Béroud persisted when the painting failed to reappear in timely fashion, and to appease him, one of the guards went to the photography studio. The painting wasn’t there. As far as the curatorial staff knew, she was in her regular spot. “La Jaconde, c’est parte,” the distraught guard told the curator on Monday. The Mona Lisa has left. She was gone for two years and eventually turned up at a hotel in Florence, where the curator of the Uffizi recognized the lady for who she was. The initial suspects: Pablo Picasso and Guillaume Apollinare, members of the avant guard art scene, though they were later exonerated. Art history is, as you can see, like so many other things in life, complicated, the answers often leading to more questions. Art theft, in particular, is a fascinating field for expert and layperson alike. I hope one of these books helps you find your own rabbit hole.